Coffee House Culture: How Coffee Changed British Society [The Past and Future of Coffee]

Great influence on 17th-century British politics and culture

If cafe culture flourished in France, it was coffee house culture that had a major influence on society in England across the English Channel for 100 years from the late 17th century.

<The interior of a coffee shop. Customers are seated at long tables drinking coffee, pipes in hand. Coffee is served from the counter on the left, and a coffee pot is being heated in the fireplace at the back. Painting from around 1700 (Trustees of the British Museum)>

<The interior of a coffee shop. Customers are seated at long tables drinking coffee, pipes in hand. Coffee is served from the counter on the left, and a coffee pot is being heated in the fireplace at the back. Painting from around 1700 (Trustees of the British Museum)> A coffee house is literally a place where you can drink coffee, a novelty that was introduced from the Arab world, and is said to have first appeared in Constantinople, Turkey in the 1550s.

From there, coffee and coffee houses spread to Venice, Italy, France, and England.

There were coffee establishments like this all over Europe, but in world history, the term "coffee house" refers to the coffee houses that became popular in England in the late 17th century.

From there, coffee and coffee houses spread to Venice, Italy, France, and England.

There were coffee establishments like this all over Europe, but in world history, the term "coffee house" refers to the coffee houses that became popular in England in the late 17th century.

The coffee culture was born in England, a country that is now known as a tea-drinking country, and is a unique culture that had a major impact on the economy, society, and culture of the country at the time.

Jurgen Habermas, a prominent contemporary German Manabu , was inspired by Hannah Arendt's concept of the "public sphere" and called the "public sphere" the place where modern citizens discussed things on an equal footing in coffee houses, reading groups, and other settings.

The "public sphere" is a place where anyone can participate and where public opinion is formed through autonomous discussion. The popularity of coffee houses in Britain was so highly regarded that it had a major impact that brought about changes in the social structure.

How was coffee drunk?

Before we talk about the origins and rise of coffee houses in Britain, let's take a look at how coffee was drunk here from the late 17th century through to the 18th century.

In Islamic countries, where coffee was widely consumed before it was consumed in Europe, the common method was to roast and crush the coffee beans and then brew them in water (initially, the beans and the surrounding husks were roasted together, but by the time it was introduced to Europe, only the beans were roasted).

In the late 17th century, coffee pots and pans were made in Turkey and the Arab world, and coffee was brewed in these pots for several people at once. This method of brewing coffee was also used in Turkish coffee houses, and it is believed that this method was introduced to Europe.

Even today, Turkish coffee is made by boiling powder, sugar, and water in a coffee pot called a cezve (ibrik).

In Islamic countries, where coffee was widely consumed before it was consumed in Europe, the common method was to roast and crush the coffee beans and then brew them in water (initially, the beans and the surrounding husks were roasted together, but by the time it was introduced to Europe, only the beans were roasted).

In the late 17th century, coffee pots and pans were made in Turkey and the Arab world, and coffee was brewed in these pots for several people at once. This method of brewing coffee was also used in Turkish coffee houses, and it is believed that this method was introduced to Europe.

Even today, Turkish coffee is made by boiling powder, sugar, and water in a coffee pot called a cezve (ibrik).

<Coffee pot called Cezve (Ibrik)>

<Coffee pot called Cezve (Ibrik)>In Europe, sugar was initially imported in small quantities and was very expensive, so in Venice people added spices instead of sugar (there was also a way of drinking it with spices in the Arab world, but spices from Southeast Asia were also very expensive).

Britain had a source of sugar in its Caribbean colonies. By developing plantations and sending slaves to increase sugar production, Britain began to import large amounts of sugar in the late 17th century.

In this way, people began to enjoy the exotic combination of coffee and sugar in coffee houses, and tobacco also became popular, and goods from the triangular trade entered people's lives here.

The rise of coffee houses

The first coffee house in England was opened in Oxford by a Jew named Jacobs in 1650, at the height of the Puritan Revolution. Initially, coffee was drunk as a medicinal drink to relieve hangovers.

The first coffee house in London is said to have been opened in 1652 by a Greek servant of the merchant Edwards, Pascha Rosé, in St. Michael's Lane, northwest of the Tower of London. In 1656, a man named James Farr opened the Rainbow Coffee House on Fleet Street, which became famous and attracted many customers. After this, the number of coffee houses increased rapidly, and by the early 18th century there were said to be approximately 3,000 in London.

The first coffee house in London is said to have been opened in 1652 by a Greek servant of the merchant Edwards, Pascha Rosé, in St. Michael's Lane, northwest of the Tower of London. In 1656, a man named James Farr opened the Rainbow Coffee House on Fleet Street, which became famous and attracted many customers. After this, the number of coffee houses increased rapidly, and by the early 18th century there were said to be approximately 3,000 in London.

Role as an information center

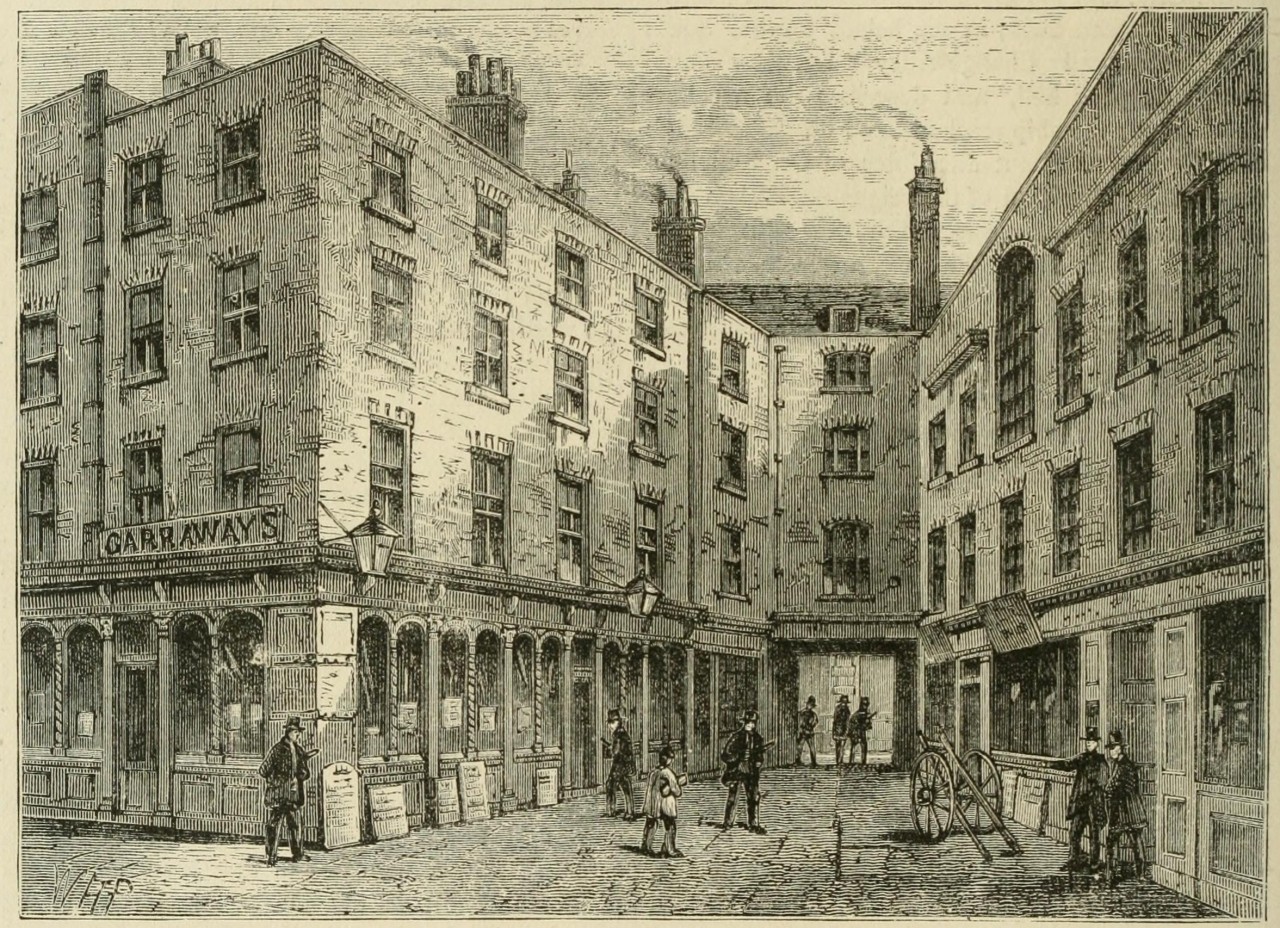

<Garraways Coffee House was located on Exchange Alley. The sign reading GARRAWAYS was displayed at the left entrance.>

<Garraways Coffee House was located on Exchange Alley. The sign reading GARRAWAYS was displayed at the left entrance.> Samuel Pepys, a famous diarist who lived in 17th century London, was a high-ranking official in the Admiralty and is known for his candid accounts of his life.

His diary reveals that he visited his favorite coffee house near London's Royal Exchange at least three times a week, sometimes twice a day, to meet friends and colleagues for appointments, or simply to listen to trade and political talks and gather information.

His diary reveals that he visited his favorite coffee house near London's Royal Exchange at least three times a week, sometimes twice a day, to meet friends and colleagues for appointments, or simply to listen to trade and political talks and gather information.

For the economic activities of the emerging bourgeoisie, which had been gaining power since the mid-17th century, coffee houses served as centers for the exchange of business information.

Merchants exchanged information with the nobles and influential people who frequented the court and Parliament, and in some cases even conducted business there. For example, at Garraway's Coffee House in Cornhill, London, the sale and purchase of ships was handled in a unique way, while sugar, coffee, timber, spices, and tea were all traded in separate coffee houses. At Jonathan's Coffee House, also in Cornhill, stock trading took place.

Merchants exchanged information with the nobles and influential people who frequented the court and Parliament, and in some cases even conducted business there. For example, at Garraway's Coffee House in Cornhill, London, the sale and purchase of ships was handled in a unique way, while sugar, coffee, timber, spices, and tea were all traded in separate coffee houses. At Jonathan's Coffee House, also in Cornhill, stock trading took place.

This place is famous for being the scene of the South Sea Bubble of 1720, when the stock prices of a trading company called the South Sea Company soared and then the bubble burst, causing a major problem at the time.

The insurance industry also emerged from coffee houses. Lloyd's Coffee House began publishing Lloyd's News, a magazine containing shipping information, around 1692, and offering it to customers, and began handling marine insurance. At the time, insurance was underwritten individually by financial institutions, but insurance for high-risk matters such as maritime transport was difficult for individuals to underwrite, so underwriters who gathered at Lloyd's began to underwrite jointly. The current Lloyd's Insurance Society and the London insurance market known as Lloyd's have their origins in coffee houses.

In this way, it was clear which coffee house you went to and what kind of information you could get, and the same could be said for political parties.

The insurance industry also emerged from coffee houses. Lloyd's Coffee House began publishing Lloyd's News, a magazine containing shipping information, around 1692, and offering it to customers, and began handling marine insurance. At the time, insurance was underwritten individually by financial institutions, but insurance for high-risk matters such as maritime transport was difficult for individuals to underwrite, so underwriters who gathered at Lloyd's began to underwrite jointly. The current Lloyd's Insurance Society and the London insurance market known as Lloyd's have their origins in coffee houses.

In this way, it was clear which coffee house you went to and what kind of information you could get, and the same could be said for political parties.

Political and economic information gathered and journalism emerged

<The Spectator, a representative daily newspaper published in London in the 18th century, published on June 4, 1711. One of the magazines enjoyed in coffee shops (British Library)>

<The Spectator, a representative daily newspaper published in London in the 18th century, published on June 4, 1711. One of the magazines enjoyed in coffee shops (British Library)> Coffee houses were cheap, costing just one penny to enter and one penny to drink coffee, and were open to all men. They were places where people could freely discuss things.

In the late 17th century, when the effects of the Puritan Revolution were still lingering, coffee houses became a place where people could discuss politics and criticize authority, offering freedom of speech. This is why it is said that public opinion was formed here. Eventually, factions began to gather at their favorite coffee houses.

Coffeehouses were places where people could obtain this political and economic information. Newspapers and magazines that compiled and printed this information were born one after another and were placed inside coffeehouses so that people could read them. Journalists who published newspapers and magazines also obtained their information from coffeehouses. Coffeehouses played a major role in the emergence of journalism.

From the late 17th century to the early 18th century, London's coffee houses were a gathering place for a diverse range of people, from noblemen to con artists. Political debates took place alongside poetry and drama criticism and literary Manabu , while business transactions were conducted and a wide variety of information was exchanged. This is how "coffee house culture" flourished.

However, the function of coffee houses was gradually replaced by clubs where only select members could gather, rather than being widely open places. Meanwhile, in the 19th century, coffee houses transformed into places where workers could gather and read newspapers and magazines.

In the late 17th century, when the effects of the Puritan Revolution were still lingering, coffee houses became a place where people could discuss politics and criticize authority, offering freedom of speech. This is why it is said that public opinion was formed here. Eventually, factions began to gather at their favorite coffee houses.

Coffeehouses were places where people could obtain this political and economic information. Newspapers and magazines that compiled and printed this information were born one after another and were placed inside coffeehouses so that people could read them. Journalists who published newspapers and magazines also obtained their information from coffeehouses. Coffeehouses played a major role in the emergence of journalism.

From the late 17th century to the early 18th century, London's coffee houses were a gathering place for a diverse range of people, from noblemen to con artists. Political debates took place alongside poetry and drama criticism and literary Manabu , while business transactions were conducted and a wide variety of information was exchanged. This is how "coffee house culture" flourished.

However, the function of coffee houses was gradually replaced by clubs where only select members could gather, rather than being widely open places. Meanwhile, in the 19th century, coffee houses transformed into places where workers could gather and read newspapers and magazines.

Reference: Akio Kobayashi , Coffee Houses: A History of Urban Life - 18th Century London, Shinshindo Publishing, 1984

If you want to enjoy coffee more deeply

" CROWD ROASTER APP"

Manabu at CROWD ROASTER LOUNGE

・Push notifications for article updates・Full of original articles exclusive to CROWD ROASTER

・Direct links to detailed information about green beans and roasters

App-only features

- Choose green beans and roasters to create and participate in roasting events・CROWD ROASTER SHOP: Everything from beans to equipment is readily available

・GPS-linked coffee map function